The Rationale For Abolishing The Police

The Rationale For Abolishing The Police

Break The Chain,

Dispel The Myth

Break The Chain,

Dispel The Myth

There is evidence that police are less effective at controlling crime than previously believed. However, they play an instrumental role in educating the public about crime prevention, reducing community fear, and potentially providing support to victims. The most effective method of countering crime is establishing, limiting, and removing the criminogenic factors, as well as launching crisis intervention models to help those in need. New York City and other major cities spend billions on police, but do they perform in accordance with expectations, perceptions, and capabilities?

#RefundTheCommunity

Police do very little to combat or solve crimes.

Police do very little to combat or solve crimes.

Police spend a short time (approximately 4%) fighting and solving violent crimes. What we know is that a growing body of research indicates police officers do not effectively combat crime. The Law Professor at NYU, Barry Friedman, writes about his observations on the tasks police are involved in. Professor Friedman points out early studies concerning urban police workload and the dispelling of the popular myth that police spend most of their time protecting the “thin blue line” of law and order.

An investigation of 3 jurisdictions in the Hudson Valley determined that violent crime was .55% of what police officers focused on. Another example of what police focus on is property crime, which represents 7.2% of their efforts. The majority of the time, law enforcement is ineffective. Aside from paperwork and personal time spent on the clock, patrolling has been calculated as taking at least 30% of paid, uniformed officers’ time. Research shows that patrolling does little to prevent crime or make civilians feel safe. Little of the work that police officers do, across the map, in small areas and in larger cities beset by high crime, provides very limited support to crime-fighting.

In Baltimore, for instance in 1999, at peak moments of crime and violence in many urban areas, Friedman described it as “one of the most abandoned parts of the United States”. During times of food deserts, low employment, and high crime, regular patrol officers focus approximately 11% of their time on crime. Observing both, violent crime and non-violent crime, police efforts to deter violence account for 5% of their duties and responsibilities. Similarly, as we look at smaller cities, towns, and neighborhoods, we realize that police attention to crime is much smaller. The majority of the time officers spend on their shifts is spent on mobilized patrol, administrative tasks, and not on actual crime-fighting or crime-solving activities.

The social costs in adolescence are real.

The social costs in adolescence are real.

The long-term negative effects of policing are well documented in a growing body of research focused on policing’s social costs. It takes courage and fortitude to observe such violence, but advocating for the justice of another person can have a significant psychological cost. As a matter of fact, research has demonstrated that events such as police violence affect children’s health and wellbeing, regardless of whether they observe them in person or online. Specifically, it affects the educational attainment and academic achievement of Black and Latino youth over the short and long term.

In response to police violence, children may display increased absenteeism by groups living in the area where police violence led to death. A significant amount of evidence indicates that students’ grades drop and persist at lower levels for several semesters – at least three semesters on average. The controversial ‘Stop and Frisk’ strategy may have a negative impact on student test performance if the target is an adolescent. The psychological hardship of educational attainment and academic achievement is directly connected to just knowing about aggressive police tactics.

It is not uncommon for Blacks and Hispanics to be unaffected by police killings when the victims are not African or Hispanic. The same way White and Asian youths do not experience state violence adversely when the victims are Black or Hispanic. Their academic achievement does not suffer as a result. Furthermore, police killings have two times the negative impact of any other type of homicide.

And while we should be concerned with “black-on-black crime”, “citizen on citizen” violence, or “neighbor on neighbor” crime, and the harm it causes these communities, it turns out that the impact of seeing or knowing about state sanctioned violence against Black and Hispanic citizens – including members who are from one’s own social group – leads to twice the harm as done when it is a citizen against citizen experience.

Furthermore, the effects of police violence extend well beyond adolescence to include the physical, mental health, and well being of adults in communities where police violence occurs. This includes the depression that mothers feel, for example, when they know their sons/daughters are being stopped and frisked by police. Research shows higher rates of depression among parents who know their child can be pursued by police. The depression one may experience due to police violence can impact people in their daily lives, employment, etc. Being powerless to stop this kind of harassment and violence as it is perceived, there is more than likely to be distress and rage.

“The Policing Paradox: Police Stops Predict Youth’s School Disengagement via Elevated Psychological Distress,” Juan Del Toro, PhD, and Ming-Te Wang, PhD, University of Pittsburgh, and Dylan B. Jackson, PhD, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Developmental Psychology, published online April 4, 2022.

Law Enforcement over-police petty crimes,

while under-policing, or neglecting safety.

Law Enforcement over-police petty crimes,

while under-policing, or neglecting safety.

Over-Policed

Police in high crime communities, or disproportionately low-income communities of color, actually do more harm than justice. When people call the police for help, they want to have some kind of confidence that the police will come, won’t make matters worse, take complaints seriously, and solve crimes (including murder) – but in low-income communities of color, there is ample evidence now that none of these expectations are being met. Instead, they experience over and under-policing.

They “over-police”, or engage in “proactive policing”, by frequently stopping pedestrians and drivers, unnecessarily and often unconstitutionally searching people. Police have revealed they use unnecessary force too often, which sometimes leads to bodily harm, death, or at the very least PTSD-like symptoms; not to mention the untold numbers of unnecessary arrests – all presumably to “prevent crime”. Although these acts have a low impact on lowering crime, what they do have huge effects on, are residents’ views of law enforcement. It is not unusual for these same communities (low-income people of color) to consider the police just another form of violent gang. And just like other gang activity, harm results… including death.

Police violence is one of the leading causes of death among young black men. There is a 1 in 1000 chance of being killed by the police. Although violent policing has shown to bring down some forms of crime, these practices actually have short and long-term negative effects on social economics and health outcomes. Many argue that these outcomes outweigh the small benefits that violent policing can accrue when considering the small impact it has on crime. Part of the negative effects policing has today is that it indirectly increases crime.

Under-Policed

Importantly, in such communities, while focusing on minor violations, police frequently engage in self-limiting activities to address concerns. Addressing minor violations with high rates in a range of harsh methods, also known as over-policing. However, when it comes to serious crimes, they often fail to show up and make people feel safe… this is underpolicing.

Victor Rios observed that police officers tend to focus on certain kinds of deviants and ignore or neglect other situations when their assistance is needed. Policing seems to be ubiquitous in the lives of many young marginalized people. However, the law was rarely there to protect them when they encountered victimization. In these communities, one gets the very real sense that the police are not there to protect you. In addition, they are not very effective at solving crimes in these communities. The vast majority of unsolved murders in the US are of Black victims, paradoxically, often, from the very communities that are being over policed.

Declining homicide rates for African-American victims count for almost half of the nation. While there was a decline in Law Enforcement’s ability to clear murders through the arrest of criminal offenders. A new study, compiled by the Non Profit Accountability Project, in Chicago found that when the victim is white, 47% of the cases were solved, which in itself is a low percentage. This is in the course of 19 months; for Hispanics, the rate was 33%, and for Black or African-Americans, the crime solving rate was less than 22%. Consequently, aggressive policing generates distrust. In some aspects, these neighborhoods are overpoliced, while others are underpoliced, with little genuine beneficial consequences in terms of solving crimes, including murders. As a result, there is a tense relationship that raises questions about the ethics of policing in these kinds of communities. who would’ve figured?

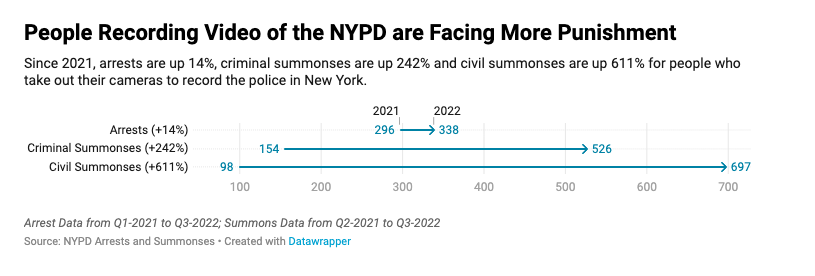

Bonus: Recording video of NYPD and getting arrested

Currently, the NYPD is required to report statistics regarding arrests and tickets for individuals who record video or photos of police interactions under the city’s new “Right to Record” law. Based on an I-Team analysis of enforcement data for the third quarter of 2022, 338 citizens were arrested for recording video of NYPD officers. This represents a 14 percent increase over the beginning of 2021.

Arrests are usually made on criminal charges such as assault, resisting arrest, obstruction, and larceny. Criminal and civil summonses are primarily issued for offenses such as drinking alcohol on public streets, noise violations, or motor vehicle infractions. A vast majority of those arrested or ticketed while recording video were people of color.

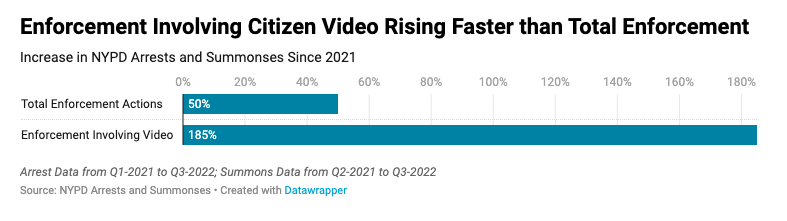

According to data provided by the NYPD, from 2021 to 2022, arrests and summonses have gone up by about 50%. During the same period, arrests and summonses involving people recording police have gone up by 185%.

What excites police is action, and that means ultimately applying violence. The people attracted to police work want that type of action — they are giddy about it.

In communities of color facing increasing economic pressure and changing norms, police responses to these quality-of-life complaints can have a negative impact.

Rio talks about how young Latino and African American boys develop their sense of self in the midst of crime and intense policing; and the politics that reinforce school-to-prison pipelines.

Police have been solving about four of every ten murders in the city, but police data show the rate is even worse when the victim is African American.

If we seek public safety,

better options are available

If we seek public safety,

better options are available

Public safety does not necessarily mean police involvement. There are several alternative ways to achieve public safety. Alternative to police, there are effective, efficient, less harmful, and cheaper initiative that perform public safety. The organization CAHOOTS, a crisis intervention service, is widely known to achieve public safety at far lower costs by effectively addressing crises, including conflict resolution.

It is known that between 28% and 50% of fatal police encounters involve mentally ill individuals. CAHOOTS’ method shows that this does not always have to be the case. Cahoots originated almost 50 years ago in Eugene, Oregon. The number of Cahoots calls in Eugene, in the year 2022 was 24,000, but only 250 of those calls prompted police backup. Effectively lowering police engagement to about 1% of all calls and potentially intervening in situations that may have quickly escalated into something far more violent if not handled appropriately.

There are several aspects associated with this, not only with individuals experiencing mental health episodes, but also domestic violence, welfare checks, substance abuse, and suicide threats. Therefore, CAHOOTS addresses a wide range of issues. It engages in trauma-informed deescalation and harm reduction techniques that result in a very positive outcome for participants. This is not even mentioning the savings, CAHOOTS’ cost-effectiveness, that can be redirected back into the community in order to support the families and communities of individuals.

Settlements

Settlements

Let’s think about what this means in regards to settlements. Settlements from police misconduct cases in large urban cities tend to be around the hundreds-of-millions. New York City tax payers spend a whopping $530M to pay off 10,500 claims against the NYPD from 2018 to 2022. In the first seven months of 2022, New York City spent over $121 million on settlements, with a significant payout of $12 million for a case involving a Brooklyn teenager who was paralyzed by police officers.

Additionally, the Police Funding Database reports several high-profile settlements, such as a $14.25 million payout in Chicago to Daniel Taylor, who was wrongfully convicted due to police misconduct and spent over 20 years in prison. Similarly, Austin, Texas, paid nearly $14 million in total settlements related to police misconduct during the 2020 racial justice protests.

These figures highlight the considerable financial impact of police misconduct on municipalities, often reflecting broader systemic issues within police departments.

CAHOOTS estimates its cost savings for police departments based primarily on the reduction in police responses. However, when considering the broader financial impact, including cost savings for cities and taxpayers from reduced settlements related to police misconduct, the benefits may be even greater. Although direct evidence linking CAHOOTS to a decrease in settlement costs isn’t readily available, the program’s effectiveness in independently managing a significant volume of calls suggests it positively impacts community relations. This, in turn, could lead to a reduction in instances of police misconduct and associated costs.

NYPD

If the Mayor and Police Commissioner prioritized early intervention, swift disciplinary processes for abusive officers, and consistent penalties as required in the NYPD’s disciplinary matrix, much police abuse–and the resulting lawsuit payouts–could be prevented. Instead, the NYPD allows officers such as Daniel Rivera, who has racked up 23 lawsuits and over half a million dollars in settlements, to continue to patrol our neighborhoods with a badge and a gun, almost guaranteeing similar abuses will continue. At the time of this update, Rivera’s employment ended October 2023.

Another settlement controversy occurred in September 2022; Eric Dym, a now-former NYPD lieutenant, quits with a long list of complaints and outstanding cases. The Civilian Complaint Review Board has requested that Lt. Eric Dym be fired during a disciplinary trial in early 2022. The 18-year veteran of the force had more pending misconduct complaints than anybody else on the force. He retired early, potentially dodging accountability.

Savings

Savings

60% of CAHOOTS clients are experiencing homelessness, while thirty percent live with severe and persistent mental illness. These individuals often find themselves frequenting emergency rooms, shelters, and jails. It’s reasonable to conclude that CAHOOTS has played a significant role in reducing arrests, jail admissions, and detentions for these individuals, along with mitigating the collateral consequences, both direct and indirect, for the individual, their family, and the community. This results in substantial cost reductions or savings for all involved.

CAHOOTS costs around $2 million to operate. It has been highly efficient, effective, and economically advantageous. Furthermore, they have resulted in significant cost savings for the police department and emergency room. During the past year, Cahoots has saved the police department up to $9 million. Additionally, they have saved $14M in ER costs because they are diverting people who otherwise would be using these services.

As a result of these organizations, larger savings could be realized. In addition to saving police and emergency room costs, and the fact that alternative interventions are relatively inexpensive, the diversion from jail that results from its activities is also significant.

These inherently systemic issues require immediate and permanent solutions. That requires a bold reduction of the role police play in our society: It is time to divest from law enforcement and reinvest in the Black and Brown communities they unjustly target.

Reminder: Source Material can be found visiting this page on your Desktop.

By investing in crucial mental health services on the front end, we can work to reduce the constantly growing number of calls to 911 regarding mental health crisis.

One in Five of every New Yorker experience Mental Illness in a given year. Hundreds of thousands of these New Yorkers are not connected to care.

Already, Cahoots is working with a number of cities — Olympia, Washington; Denver, Colorado; New York; Indianapolis, Indiana; Portland and Roseburg, Oregon.

If the event is primarily a behavioral issue and there’s no imminent danger, then there should be a preference to stack the deck in favor of a clinical team response.

Other Models

Other Models

By prioritizing young people and investing in their education, training, and diverse skill development, we can notably decrease crime rates linked to adolescence and the transition into adulthood. Addressing substance abuse issues, alleviating financial hardship, and providing income supplements can effectively stabilize individuals and their families. Furthermore, investments in community organizations and institutions offering such support services play a crucial role in reducing crime and violence. This approach allows for a decreased reliance on law enforcement resources, yielding significantly improved outcomes for communities.

Various emerging models are tackling similar challenges encountered by certain communities and have demonstrated effectiveness in addressing these issues. For instance, CURE Violence has successfully reduced violence within communities grappling with high rates of violence, both domestically and globally. Additionally, investments in environmental strategies, such as the reclamation of vacant lots, have been proven to decrease crime, including violent crime.

Monica C. Bell

(Yale Law School)

Monica C. Bell

(Yale Law School)

Monica C. Bell challenges the deeply ingrained notion that police equate to public safety. As a Yale Law School professor, Bell argues that our heavy reliance on police for societal order is a modern construct that often does more harm than good, particularly in marginalized communities. Her research suggests that we need to denaturalize the police, revealing their role in perpetuating oppression rather than protecting communities. Bell advocates for reimagining public safety through community-led initiatives that avoid the historical and ongoing repression experienced under traditional policing.

Danielle Allen

(Harvard University)

Danielle Allen

(Harvard University)

Danielle Allen, a distinguished scholar at Harvard University, critiques the superficial reforms often proposed to address police misconduct. She contends that these measures fail to tackle the structural racism embedded within policing institutions. Allen’s work emphasizes the need to dismantle the current policing system entirely, proposing a transformative approach to justice that centers on community empowerment and restorative practices. Her controversial stance insists that true safety cannot coexist with the deeply flawed and racially biased policing models in place today.

Cornell W. Brooks

(Harvard Kennedy School)

Cornell W. Brooks

(Harvard Kennedy School)

Cornell William Brooks, a professor at Harvard Kennedy School, offers a pointed critique of the traditional policing system’s failures. As a former president of the NAACP, Brooks draws on his extensive experience in civil rights advocacy to highlight how police departments systematically fail to protect Black communities while disproportionately subjecting them to violence and surveillance. He calls for the abolition of the police as a necessary step toward creating equitable public safety measures that truly serve all citizens. Brooks’ controversial yet grounded argument insists that policing as we know it is irredeemably broken and must be replaced with community-led safety initiatives.

Vesla M. Weaver

(Johns Hopkins University)

Vesla M. Weaver

(Johns Hopkins University)

Vesla M. Weaver of Johns Hopkins University provides a scathing analysis of how policing exacerbates social inequality and undermines democracy. Her research exposes the profound disparities in how different communities experience policing, with marginalized groups facing constant surveillance and brutality. Weaver argues that the police are not just failing to prevent crime but are actively contributing to social harm and injustice. She advocates for radical changes, including the abolition of the police, to pave the way for more democratic and just systems of community safety and support.

I extend my heartfelt gratitude and dedicate this article to Sandra Susan Smith, the Daniel & Florence Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice at Harvard Kennedy School and the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. Professor Smith’s profound insights into urban poverty, joblessness, race and ethnicity, social networks, and criminal justice policy have significantly influenced the direction and focus of this work. Her research exposes the systemic failures of the policing system, revealing how it perpetuates social inequality and fails to address the root causes of crime. Smith’s compelling argument insists that true justice and public safety can only be achieved by dismantling the current policing structure and investing in community-driven solutions that address the underlying socio-economic factors contributing to crime. Her work is a call to action for a radical rethinking of public safety, rooted in equity and restorative justice.

I extend my heartfelt gratitude and dedicate this article to Sandra Susan Smith, the Daniel & Florence Guggenheim Professor of Criminal Justice at Harvard Kennedy School and the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. Professor Smith’s profound insights into urban poverty, joblessness, race and ethnicity, social networks, and criminal justice policy have significantly influenced the direction and focus of this work. Her research exposes the systemic failures of the policing system, revealing how it perpetuates social inequality and fails to address the root causes of crime. Smith’s compelling argument insists that true justice and public safety can only be achieved by dismantling the current policing structure and investing in community-driven solutions that address the underlying socio-economic factors contributing to crime. Her work is a call to action for a radical rethinking of public safety, rooted in equity and restorative justice.

CONTRIBUTORS

CONTRIBUTORS

“A community that populates solidarity is a community that is protected, not policed.”